CRISES has been a leading international research group for many years and is at centre of the URV’s intense research into security and privacy in computer and digital environments, with the management of artificial intelligence representing a key challenge

“It is a constant race between the cyber-attackers and those of us who work in digital security, in which it is a question of who is faster and smarter”, states Oriol Farràs, one of the members of the URV’s CRISES research group, an international leader in cybersecurity. Farràs and his colleagues face a challenge: to stay ahead of the development of quantum computers, which, according to some forecasts, will eventually replace conventional computers and render current cybersecurity protocols useless. Quantum computing overlaps and interweaves data because of its ability to be in two states simultaneously, which in turn allows it to solve very complex calculations. If it continues to evolve, it is expected to create powerful and increasingly extensive computers that could decrypt encrypted information much more easily than conventional computers.

“It is therefore a question of finding alternative methods, new security standards that remain difficult to decrypt and that are not vulnerable to cyberattacks”, explains Oriol, who also highlights the threat to security posed by quantum computers finding entry points to blockchains (shared ledgers of financial transactions and data), to messaging applications or to secure communication channels with browsers, in addition to the forging or fraudulent use of digital signatures, with all the dangers that that entails.

Consequently, Farràs’ work focuses, on the one hand, on finding mathematical problems to generate increasingly robust encryption methods and, on the other hand, on working with the Barcelona Supercomputing Center to develop accelerators for new security standards, which are currently very slow. “We have to ensure that post-quantum security does not bring with it long delays or negative repercussions for digital communication,” he says.

La cursa és constant, sense final, ja que cal garantir la seguretat sabent que els mateixos avenços tecnològics The race is continuous, without end, as the researchers work in the knowledge that the very technological advances on which their research is based are also those that facilitate the attacks. New threats must constantly be neutralised as they emerge.

Oriol Farràs’ work is one of the main research lines of the CRISES-Security & Privacy group of the URV’s Department of Engineering and Mathematics, which has been researching cybersecurity and privacy for more than two decades. “There was a moment when the internet became generalised, everyone became connected, and that is when people realised that there were cybersecurity problems. Viruses and increasingly sophisticated attacks appeared, and that was when we saw the need to carry out in-depth research”. So explains Josep Domingo-Ferrer, director of the research group and the most cited researcher in Spain in cybersecurity and the twenty-eighth most cited in the world. At the URV, Domingo-Ferrer also coordinates the CYBERCAT, the Catalan cybersecurity research centre, which brings together seven research groups from six universities around the country.

“More and more of our lives take place online. In the physical world, we use the police and army to provide security, but now we also need to secure the online world. Without security there is no civilisation, that is why it is essential, but at the same time it is also necessary to protect privacy, to make sure that your life is not exposed,” explains Domingo-Ferrer. In fact, according to him, “you have to be more jealous of privacy online than in the physical world because you can’t see who is watching you, and whoever is watching you may not have good intentions”.

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a tool that makes things much easier at all levels, but it also opens a new front in the quest for security and privacy. In this regard, Josep Domingo-Ferrer and another professor in the group, David Sánchez, are focusing their research on making AI trustworthy, that is, on ensuring that it cannot be attacked to distort its learning and that the data used to train it and which are generally private cannot be shared for any other purpose.

The race is constant, without end, as the researchers work in the knowledge that the very technological advances on which their research is based are also those that facilitate the attacks

They work, for example, on the so-called right to be forgotten. “The General Data Protection Regulation says that everyone has the right to have their data removed from computer systems so that Google, for example, does not return results that you don’t want it to return”, explained Domingo, who said that this right is more difficult to guarantee in language models such as ChatGPT because they have been trained using all the available data, making it more difficult to destroy data that someone asks to be deleted at a given moment: “Completely eliminating these data would mean retraining the model from zero, which would be very costly. There are methods of untraining that can do this more quickly, but they do not guarantee total removal. What we are looking for are models that are very fast but that also give maximum privacy protection”.

The balance between security and privacy is also one of Rolando Trujillo’s concerns. He is working with communications companies on a project to verify whether an anti-disinformation system that seeks to authenticate images and videos circulating on the internet actually meets its objectives whilst, at the same time, protecting privacy: “Because a signature is used to validate the image, privacy is compromised as this enables the person who has taken the photograph to be identified. What we need to do is to find a balance between privacy and contrasted information”.

Trujillo’s research mainly focuses on finding formal methods to check the security of a product automatically: “Any computer system undergoes a test period to find out whether the software implementation and design have the required security properties; that is to say, that it does not have additional functions that can provide entry points for hackers. It is easy to define what we expect from software, but not so easy to define what we do not expect. We therefore try to determine mathematically that a given software, such as the messaging application Whatsapp, has only the properties that we expect; that is, that it remains robust against attacks by hackers“.

In general, the types of software that Trujillo tries to verify are security protocols used for messaging applications or payment cards, for example, those that verify the proximity between two devices to ensure that the payment is being made at the correct terminal.

CRISES researchers seek a mathematical demonstration to obtain an objective assessment of a system’s security level. These formal verification tools explore all the possible states of the software; for example, in a messaging application these would include when the message is sent, when it is replied to, when the application is connected to the internet, and so on. And when the tool’s mathematical formula detects an invalid state that violates a security property, it gives a warning and highlights the path that it has found to prevent its use by hackers. “Through computer reasoning, our work helps to uncover very subtle errors that escape human eyes and that could be entry points for an attack,” he explained.

The difficulty is that a certain level of abstraction is required because the real world is very difficult to define precisely; that is, the tools are often unable to prove whether a piece of software has a certain security property because they cannot resolve undecidable situations, that is, situations that are neither true nor false but which instead have nuances. This makes it necessary to help the tools, to reinforce them, for example by means of theorems. “It is a combination of computation and mathematics,” says Trujillo, who was born in Cuba and who, after long stays in Luxembourg and Austria, has returned to the URV where some time ago he defended his doctoral thesis on security protocols that do not increase the cost of the devices.

The expansion of the internet and its implementation in everyday objects not only increases technological possibilities, but also the need for researchers to keep up their research and stay ahead of bad actors. This is the case for Jordi Castellà, an expert in connected vehicle safety. For example, he deals with how cars are allowed access to low emission zones in urban areas through the use of many cameras that read and record number plates. “Privacy is very much compromised by these cameras, as they make it possible to track the movements of many people, where they live, when and where they go to work and so on. Our aim, therefore, is for permission to be obtained via mobile devices, which can be used to show that a person has the necessary permission but without giving away their identity. Then, anyone who enters without permission would have their identified revealed”. They would be punished by having their privacy removed. According to Castellà, the same vehicle cameras could be used to monitor other vehicles and to report irregular situations.

All the projects are ready to be applied when they are needed by the public sector, which closely follows all developments in cybersecurity and privacy and regards the URV’s CRISES group researchers as leaders in the field

The smart grid also represents a risk to privacy through the use of solar panels that turn energy consumers into producers. “Data on consumers’ historical consumption has to be gathered to make forecasts, but if this data is too public, it could end up revealing every movement that is made in every house. However, if the data collection process is automated with intelligent methods, the necessary information can be gathered whilst protecting the privacy of each user,” Castellà explained.

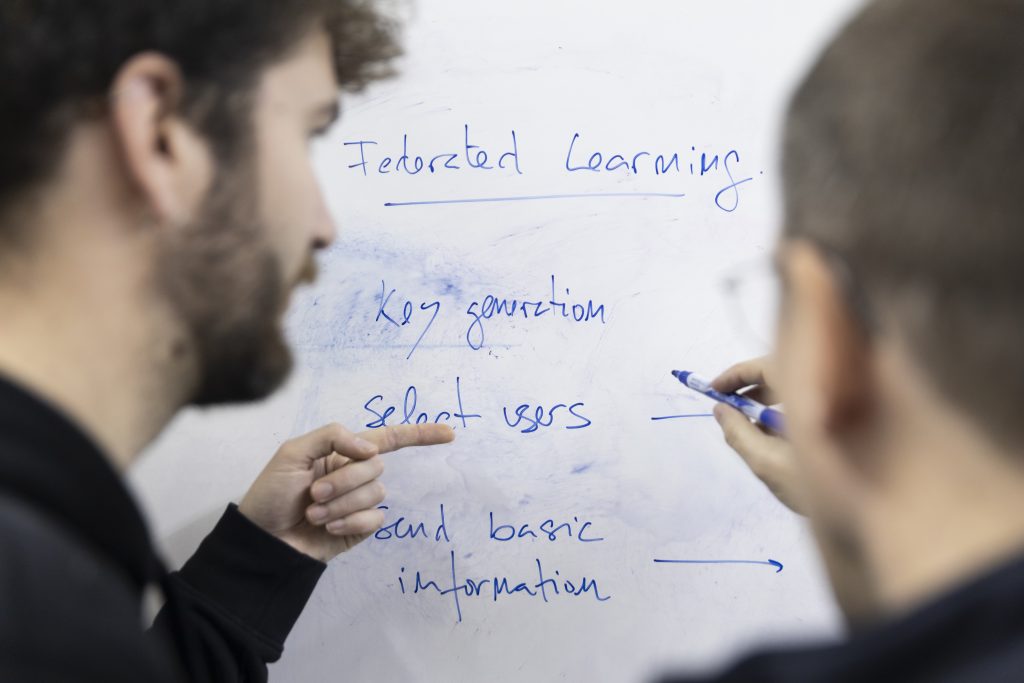

For example, this could be achieved by training artificial intelligence with masses of consumption data, which would be provided by users themselves without the need for them to reveal their identity. This is known as federated learning. The greater the amount of data, the more accurate the forecasting and the consequent automatic efficiency adjustments, and the less visible the individual data.

Nevertheless, in order for the data that feed AI to be truly reliable, it is necessary to have permission and to know the traceability (where they come from, what conditioning factors they have, etc.), whilst at the same time ensuring privacy. This can be achieved using smart contracts between users and companies because they make it clear what permission has been given and they can be cancelled or updated at any time. “The challenge is to maintain traceability so that the data remain reliable, but without revealing their origin. That is, we must ensure both traceability and privacy at the same time,” Castellà concluded.

Much of this research is done in collaboration with companies, who provide information for the studies, and with the public sector, which closely follows all developments in cybersecurity and privacy and regards the URV’s CRISES group researchers as leaders in the field. “The hope is that the knowledge we develop internally through both academic and private sector activity will end up being used by companies and the public sector,” says Rolando Trujillo. In terms of academic activity, the URV has been teaching the University Master’s Degree in Computer Security Engineering and Artificial Intelligence for years. “All our projects are ready to be applied when needed to all areas of the public sector,” says Jordi Castellà.

Cybersecurity is of great importance in the current international context, characterised by polarised blocs and latent political and terrorist threats. It is for this reason, as Josep Domingo-Ferrer reminds us, that the potential civilian and military uses of the research are very much taken into account when it comes to project funding. Domingo-Ferrer is clear that values must be preserved, not only privacy but also others such as equality, non-discrimination, respect and dialogue, and that at a time when populism and state rearmament are on the rise, Europe that must step up to protect them. But he also warns that over-zealous exaggerations about, for example, the ethical implications of artificial intelligence can be counterproductive and could cause Europe, the weakest bloc technologically speaking, to continue to fall behind the others.

Domingo-Ferrer explains that he and David Sánchez are leading a line of research to establish what exactly are the real technological and scientific dangers of AI and data management, so that those who manage it can make realistic laws. In fact, Europe has shown itself ready to relax the laws on artificial intelligence because, as Josep Domingo points out, the risks to privacy have been found to be exaggerated and to have generated unjustified alarm. In short, this is a long-distance race in which values should always be kept at the forefront but without becoming an obstacle that gives an advantage to rivals.