27/11/2025

Crouzon syndrome diagnosed in a knight from the Order of Calatrava, killed in battle over 600 years ago

A URV-led research team has studied some remains that are unique in the field of archaeology: an adult individual with craniosynostosis, a severe congenital cranial deformity, and who lived at the castle of Zorita de los Canes between the 12th and 15th centuries

A URV-led research team has studied some remains that are unique in the field of archaeology: an adult individual with craniosynostosis, a severe congenital cranial deformity, and who lived at the castle of Zorita de los Canes between the 12th and 15th centuries

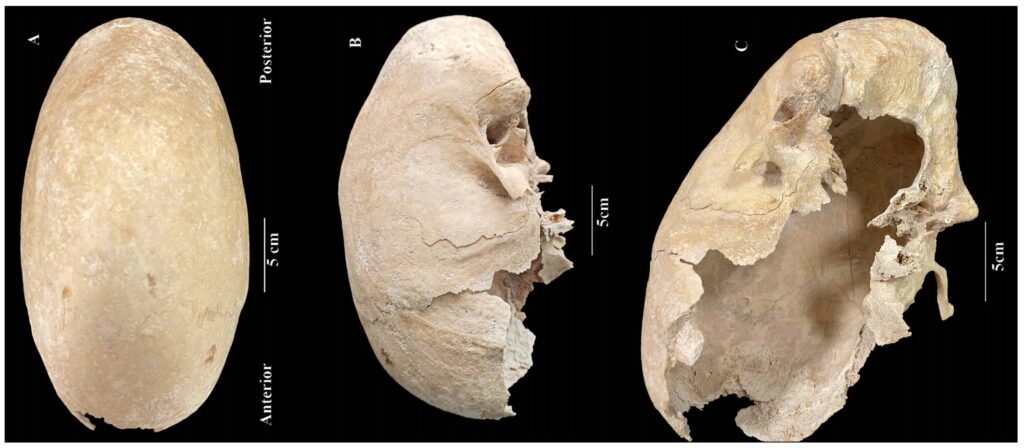

For the ArchaeoSpain research team, it was a day just like any other on their dig at the castle of Zorita de los Canes (Guadalajara). They were working at the Corral de los Condes, where some knights from the Order of Calatrava are buried, when they came across some highly unusual human remains. Accompanying an apparently normal adult skeleton, was an extraordinarily narrow and elongated skull, 23 centimetres long and only 12 centimetres wide. Who was this individual and how did they survive to adulthood? What caused such a severe cranial deformity? What role did they play in the Order of Calatrava? To answer these questions, the team sent the skeleton to the laboratory of Carme Rissech, a researcher in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences at the URV.

“I’m always very sceptical, like Saint Thomas,” says Rissech, recalling the moment when she was told they were sending her the bones of some knights from Calatrava. When faced with cases like this, Rissech always follows a set procedure: first, to determine the individual’s identity, she carries out a morphological study. She takes measurements of the remains and determines their sex. She explains that “just by looking at the skull you can tell if it’s a male or female”, but also that that this information can be obtained from “the coccyx, the pelvis and the birth canal”. She then looks at the markers of stress and age, which are the marks that physical activity and the ageing process leave on the skeleton’s bones. These indicators give researchers clues about the individuals’ profession or lifestyle and an estimate of their age at the time of death. Finally, Rissech examines the skeleton for clues as to the cause of death, such as penetrating injuries, lacerations, contusions, etc.

A knight killed in battle

Rissech’s morphological study concluded that the remains belong to a man who was around fifty years old at the time of his death, which occurred sometime between the 12th and 15th centuries. She identified marks of physical stress that indicate that he was “most likely” a member of the Order of Calatrava: “The insertion marks of the deltoid and biceps muscles on the right arm are identical to those found on the bones of other knights.” This information is also consistent with other stress indicators that indicate regular horse riding, for example the increased roughness of the linea aspera located on the front of the femur, and the sharper edges on the acetabulum, the part where the femur meets the pelvis.

But what allows Rissech to state this with confidence are the lesions on the skeleton: a penetrating wound to the temple (the point where the sphenoid, frontal, temporal and parietal bones of the skull meet), another penetrating wound to the nape of the neck (the occipital bone), and a large contusion on the left tibia, which shows concentric fractures that are again very characteristic of this kind of trauma. “These are very common injuries in the remains of medieval warriors killed in battle, and they are different from those found in individuals who died during sieges. The former may be found in various parts of the body, whereas the latter usually only affect the skull. In the case of this individual, the injuries occurred when the bone was fresh and they show no signs of healing, which leads us to believe that they most likely caused his death,” the researcher points out.

A unique case in archaeology

And the skull? Well, after studying it in detail, Rissech reveals that it presents a very severe case of craniosynostosis, a condition where one or more cranial sutures prematurely fuses during childhood and prevents normal growth and development. This is why, according to the researcher, it is extraordinary that this individual reached adulthood: “It is the first time we have found a case like this; we have identified the remains of infants with this condition but we have never seen it in adults, and even less so in knights; it is something unique and exceptional”.

The skull—which is 23 centimetres long by 12 centimetres wide—shows significant damage to the jaw area, which must have prevented the man from moving it much. This hypothesis is consistent with the amount of dental plaque that it displays. All of this could be related to the lack of teeth on the right side of the mouth: “We can’t prove it, but we believe they may have been extracted to enable the man to eat,” the researcher conjectures.

Given all these details, the research team has tried to diagnose which syndrome caused his craniosynostosis. To do this, they carried out a differential diagnosis, a clinical process that allows doctors to distinguish between two or more diseases with similar symptoms, ruling out those conditions they know for certain the individual did not have until they find the only one that is compatible with the evidence. In this case, they were able to rule out syndromes involving deformities in other parts of the skeleton or a shortened life expectancy and were thus able to arrive at the most likely diagnosis: Crouzon syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that causes syndromic craniosynostosis.

According to Carme Rissech, this diagnosis makes a great deal of sense: “In most cases, Crouzon syndrome does not involve serious cognitive impairments and does not affect life expectancy.” She goes on to state that to be part of the Order of Calatrava, this knight had to be functional and contribute to the community, although he may have needed help with certain tasks, such as eating. But despite any difficulties he may have had, the evidence suggests that he rode a horse and wielded a sword, and when the time came to enter battle, he would have done so just like his brothers.

Reference: Rissech, C., Creo, O., Revuelta, B., Cobo, S., Urbina, D., Urquijo, C., Banks, P., & Lloveras, L. (2025). An Ultradolichocephaly in a Knight of the Order of Calatrava from the Castle of Zorita de los Canes (Guadalajara, Spain) Dated Between the 13th and 15th Centuries. Heritage, 8(10), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100414