24/11/2025

More buildings, more heat: quantifying the effect of the urban texture on heat islands

Research from the Universitat Rovira i Virgili examines how the make-up of cities helps to make them hotter than nearby rural areas

Research from the Universitat Rovira i Virgili examines how the make-up of cities helps to make them hotter than nearby rural areas

A total of 1,153 people died in Catalonia in 2024 from heat-related causes, according to a study by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health. And in recent years it has been observed how the climate crisis particularly affects the Mediterranean region: weather phenomena such as cold snaps, persistent droughts and heatwaves are increasingly frequent and intense. “Heat kills, especially in cities, where the average temperature tends to be higher,” warns Alexandre Fabregat, a researcher in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV). It is not that cities have different weather conditions from the surrounding areas, it is that the cities themselves cause this effect, which is known as the ‘urban heat island’.

The urban heat island effect is, by definition, the difference between the temperature recorded at a given point in the city and the temperature that would be recorded if the city did not exist. Since the latter cannot be measured directly, the temperature of nearby rural areas is used as a reference. But why are cities hotter than their rural surroundings? Fabregat explains that this is due to three determining factors: firstly, construction materials, such as concrete or asphalt, are very efficient at absorbing and storing solar radiation during the day and then releasing it during the night; secondly, the urban fabric modifies air currents and their ability to dissipate the accumulated heat; finally, cities are home to high concentrations of residual heat sources such as air conditioning units or internal combustion vehicles.

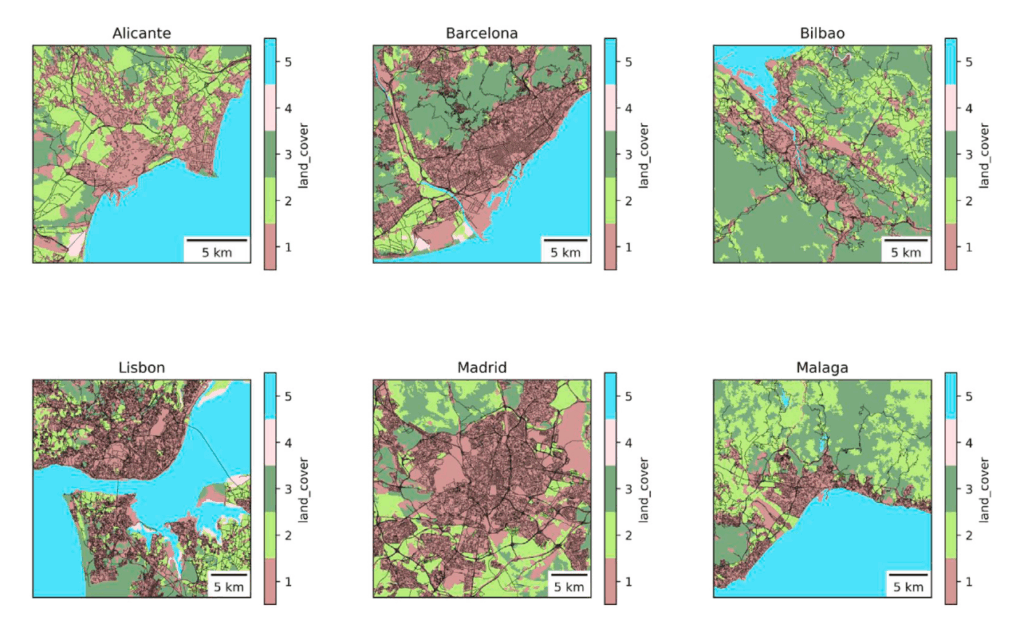

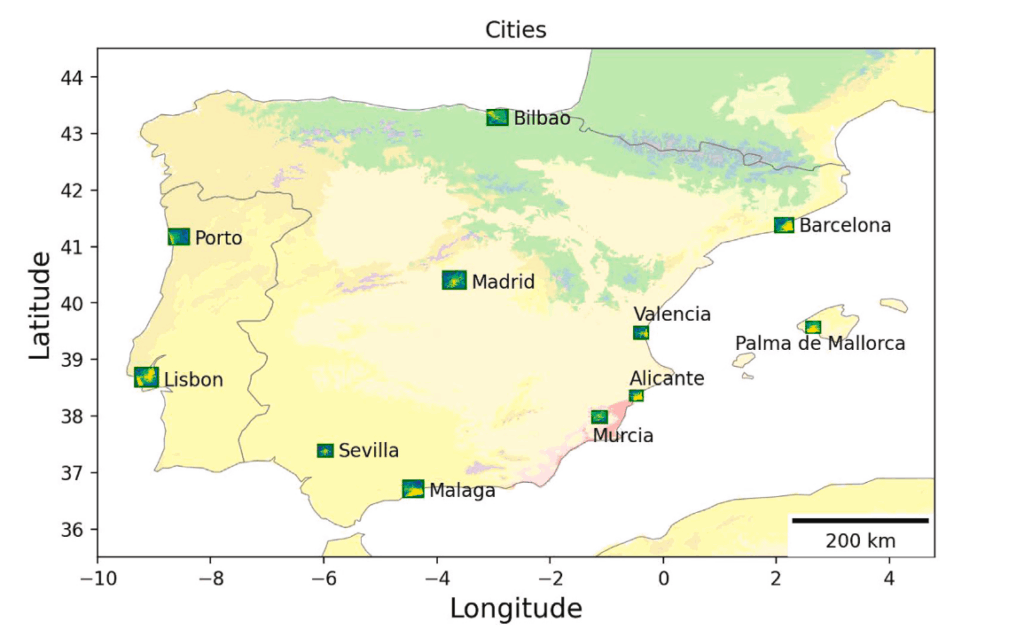

In order to quantify how these factors help exacerbate the urban heat island phenomenon, researchers from the URV’s ECoMMFiT research group have studied the effect in 11 cities in the Iberian Peninsula. To do this, they worked with UrbClim, a climate model managed by the European Union which enabled them to simulate temperature values in each hectare—a 100×100-metre “pixel”—of the city over the course of a year. “These are very precise models; they prove to be very reliable when compared with readings from real weather stations,” explains Fabregat.

Once they had obtained these values, they compared them with the average temperature of nearby rural areas at the same altitude in order to estimate the intensity of the heat island. Finally, to determine the effect of the urban texture on temperature, the study drew on another European dataset called GHSL so that they could include data on built-up height, the amount of urbanised land, vegetation cover and population density for each “pixel” of the city.

Heat, especially in the early morning

The research team was able to confirm that the urban heat island effect is relatively mild during the day, but more noticeable during the early hours of the morning, especially between three and four o’clock. According to Fabregat, in some cases the temperature difference can be up to 7°C in specific locations: “From a health and quality of life perspective, it has a major impact at a very important time of day when people are resting.”

The study’s results revealed a 0.34°C increase in the average temperature for every 10% increase in the amount of built-up land; that is, the more buildings, the more heat. “It could be argued that when buildings cast shade, they help to cool the city; the data, however, indicate that the heat-storing capacity of building materials and the obstruction of air currents more than counteract any shade they may produce,” reflected the researcher.

Furthermore, the researchers demonstrated that the height of buildings also contributes to the phenomenon: for every additional metre of height built (on average), they found an increase in the average temperature of 0.1°C. Population density and its related human activities were also found to have an effect, with an increase of 0.08°C for every 1,000 additional inhabitants per square kilometre.

But it is not all bad news. The study’s results also reveal that vegetation cover helps to cool the environment. More specifically, the average temperature drops by 0.11°C for every 10% increase in covered area. However, the URV researchers sounded a note of caution: “We found that the cooling capacity of plant cover is significantly more limited than in other studies”. In this regard, they warn that its role within the urban ecosystem and the extent to which it can be a useful tool for mitigating the effects of the heat island must continue to be studied.

A useful tool in urban planning

The climate models and datasets used in this research provide the scientific community with information on a large number of cities around the world. This paves the way for further study of the phenomenon in other climatic and cultural contexts, environments where the architecture, building materials or urban planning are different from those found in the Iberian Peninsula. According to Alexandre Fabregat, it is also about “providing tools that can be useful in urban planning processes to help people to make evidence-based decisions”.

Reference: Josep A. Ferré, Anton Vernet, Alexandre Fabregat, Predicting the impact of the urban texture on the Urban Heat Island intensity using Machine Learning: The case for the Iberian Peninsula, Urban Climate, Volume 62, 2025, 102527, ISSN 2212-0955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2025.102527