Press notes 01/10/2024

Each mussel grown in Catalonia contains an average of 9 microplastics

A research project involving the URV has studied the presence of microplastics in bivalves cultured in Catalonia and has determined the effects of a purification process on the levels of these particles in mussels, oysters and clams

A research project involving the URV has studied the presence of microplastics in bivalves cultured in Catalonia and has determined the effects of a purification process on the levels of these particles in mussels, oysters and clams

Microplastics are particles between a thousandth of a millimetre and half a centimetre in size and made up of polymers usually synthesised from petroleum products. They are pollutants derived from human action and are present in almost all the world’s ecosystems. Because they come in all shapes and sizes, they can enter the food chain very easily; unsurprisingly, therefore, they have been detected in products for human consumption and oral exposure to these particles through the human diet has been confirmed. In view of this situation, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) considers microplastics “a potential food safety issue“, with particular concern regarding seafood.

Researchers at the URV’s Centre for Environmental, Food and Toxicological Technology (TecnATox) have experience studying the presence of microplastics in bivalves farmed in Catalonia. In their research, they have determined the impact of depuration time on the levels of microplastics in mussels, oysters and clams. They also analysed the size, morphology and chemical composition of these artificial particles present inside the specimens. “We chose to study these animals because they obtain their food by filtering water; this means that they are prone to collecting any microplastics that might be present in their local environment,” explained Joaquim Rovira, a researcher at the URV’s Department of Basic Medical Sciences. Rovira also pointed out that they are consumed whole, so that any microplastics they may have accumulated are ingested by humans too.

The results revealed that on average each individual mussel contained almost nine microplastics before they were submitted to the depuration process, which is designed to eliminate toxins and pathogenic micro-organisms from molluscs and consists, among other things, of submerging the animals in disinfected water for a period of time that varies depending on the mollusc and its area of cultivation. When the animals were subjected to 24 hours of depuration, the quantity of microplastics inside them was reduced by 50%, a level which remained stable after 48 hours. In the case of oysters, eleven microplastics were detected per animal, a figure that was reduced by 25% after 72 hours of depuration and almost 50% after 96 hours. Finally, in clams, an average of one and a half microplastics per individual was found before depuration. After five hours, the levels were reduced by more than 30%.

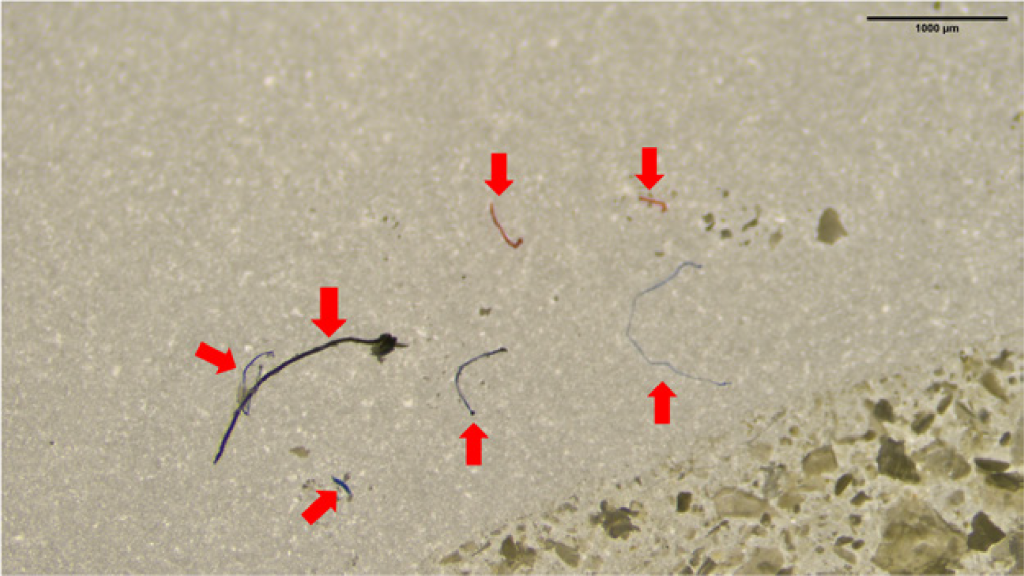

Most of the microplastic particles found in the specimens are fibres, although fragments and films have also been detected. Oysters tend to accumulate larger microplastics than mussels, and mussels larger microplastics than clams. The composition of the polymers coincides with the most commonly used types of plastics: polyester and synthetic cellulose, widely used in textile manufacturing. are the most common in terms of fibres, whereas polyethylene, polyethylene terephthalate and polyurethane were the most common polymers in the form of films and fragments.

According to the researchers, microplastics reach the sea mainly from land-based activities such as industrial and domestic processes, wear and tear on tyres, etc. One of the main sources of microplastics is synthetic clothing, the fibres of which are released into the sea through washing machines. “Wastewater treatment plants cannot retain them,” warned Rovira. Moreover, larger plastic objects, once they reach the sea, can break up into smaller pieces, which are then ingested by aquatic organisms.

This research has been carried out by the Tecnatox research centre of the URV, in collaboration with researchers from the University of Florence (Italy) and the University of Barcelona. Funded by the Catalan Food Safety Agency (ACSA) of the Department of Health of the Catalan Government, you can consult the full version on their website.