07/09/2023

Research by the URV finds different optimal points of ripening for fruit to extend its commercial possibilities

The study by the Department of Analytical Chemistry and Organic Chemistry, which uses an extensive sample and a rapid analysis technique that does not damage the fruit, aims to help the primary sector diversify

The study by the Department of Analytical Chemistry and Organic Chemistry, which uses an extensive sample and a rapid analysis technique that does not damage the fruit, aims to help the primary sector diversify

The threefold objective of extending the commercial possibilities of fruit to help the primary sector, increase its consumption and prevent it from being thrown away is the starting point of a research project by the URV’s Department of Analytical Chemistry and Organic Chemistry. The project aims to help producers find quickly and easily the different optimal ripening points of fruit so that they know when it should be harvested for the use to which it will be put.

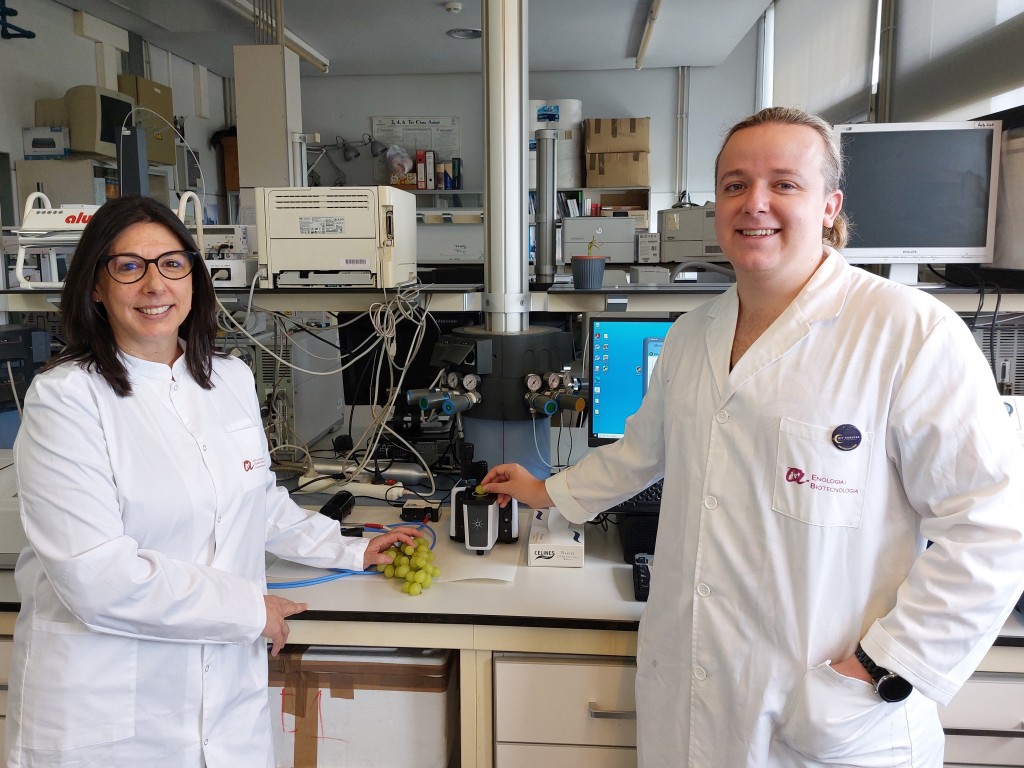

The research group Chemosens (Chemometric and Sensometric for Analytic Solutions), in collaboration with the Institute of Research and Food Technologies and the Instituto Tecnológico Agrario de Castilla y León, uses a novel, non-invasive and portable technique that makes it possible to determine the ripeness of fruit in the same field, and specifically of grapes, the focus of the study.

“In the case of grapes, we nearly always need to find the optimum point for vinification. But if we set different ripening times, the grapes can be used to make juices or snacks, or be eaten directly”, explains the researcher Montserrat Mestres, who points out that thanks to this research, those winegrowers who sometimes leave the grapes on the vine because it is not worth the trouble harvesting them or because there is a surplus “will be able to wait for another optimal moment of ripeness and use them for another purpose.”

The first step is to obtain information that is representative of the ripeness of the whole vineyard so “parameters such as the amount of sugars and the acidity must be determined from an exhaustive sampling that considers the orientation and the position of the vine within the vineyard, each bunch on the vine, and even each grape in the bunch so that the conclusions are reliable”, explains Daniel Schorn-García, another of the researchers involved in the project, who use infrared spectroscopy to achieve these goals.

Classic analysis requires samples to be transported to the laboratory and, once there, the techniques used are expensive in terms of time and money. This is why the URV researchers believe infrared spectroscopy is an interesting alternative: it is fast, does not require any reagents and can measure the fruit in the field without spoiling it.

As Schorn explains, the technique is based on the interaction of a beam of infrared light with the molecules in the sample, in this case, grapes. “This energy causes all the bonds of the molecules to vibrate in a particular way. These vibrations can be subjected to mathematical or chemometric treatment to find information about their composition and the proportion in which each molecule is found”, he says. With such precise information, and considering the time and position in which each grape was picked, producers can determine when it is best to harvest which fruit depending on the use to which it will be put.