29/01/2020

Systematic manufacture of skull cups was a ritual from the end of Palaeolithic to Bronze Age

It has been revealed through the study of cut marks on fossils from Atapuerca and other European sites. The research has been led by Francesc Marginedas, a student of the Erasmus Mundus Master’s in Quaternary Archaeology and Human Evolution Degree at the Rovira i Virgili University

It has been revealed through the study of cut marks on fossils from Atapuerca and other European sites. The research has been led by Francesc Marginedas, a student of the Erasmus Mundus Master’s in Quaternary Archaeology and Human Evolution Degree at the Rovira i Virgili University

The ritual use of human skulls has been documented in several archaeological sites of different chronologies and geographical areas. This practice could be related to decapitations for obtaining war trophies, to the production of masks, as decorative elements (even with engravings) or to what is known as skull cups. In fact, some ancient societies considered that human skulls possessed powers or life force, justifying sometimes its collection as evidences of superiority and authority during violent confrontations.

Different signals preserved on the bones help us to recognize possible ceremonial practices. The most common modifications related to the ritual treatment of skulls are those produced by stone tools or metal knives, that is, cut marks, during scalp removal. This practice is archeologically well documented among American Paleo-Indians, for example, who show circular arrangements around the head as signs of this type of practices.

n Europe, skull cup have been identified in assemblages ranging from Upper Paleolithic, about 20,000 years old to the Bronze age, about 4,000 years ago. The meticulous fracturing of these skulls suggests that they are not only related to the need to extract the brain for nutritional purposes, but that they were specifically and intentionally fractured for obtaining containers or vessels. This is evidenced in a study carried out by a team of researchers from IPHES (Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution), the URV (Rovira and Virgili University of Tarragona) and the Natural History Museum in London (NHML), which have developed a statistical analysis to assess whether the cut marks on skull fragments of the TD6.2 level of Gran Dolina in Atapuerca (Spain), Gough’s Cave (Great Britain), Fontbrégoua (France), Herxheim (Germany), and la Cueva de El Mirador also in Atapuerca respond to a systematic processing.

The results conclude that these striate certainly respond to a specific pattern in the most recent chronological sites, showing treating skulls practices that were perpetrated during almost 15,000 years. The results of this research have been published in the prestigious Journal of Archaeological Science. The study has been led by Francesc Marginedas, who is currently pursuing the Erasmus Mundus Master in Quaternary Archaeology and Human Evolution (taught at the URV) and doing his research work in IPHES under the supervision of Dr. Palmira Saladié. Marginedas studied the degree in “Cultural Anthropology and Human Evolution”, jointly taught by the URV and the Open University of Catalonia (UOC). It was while he was receiving these courses that he began his research career, specializing in this subject.

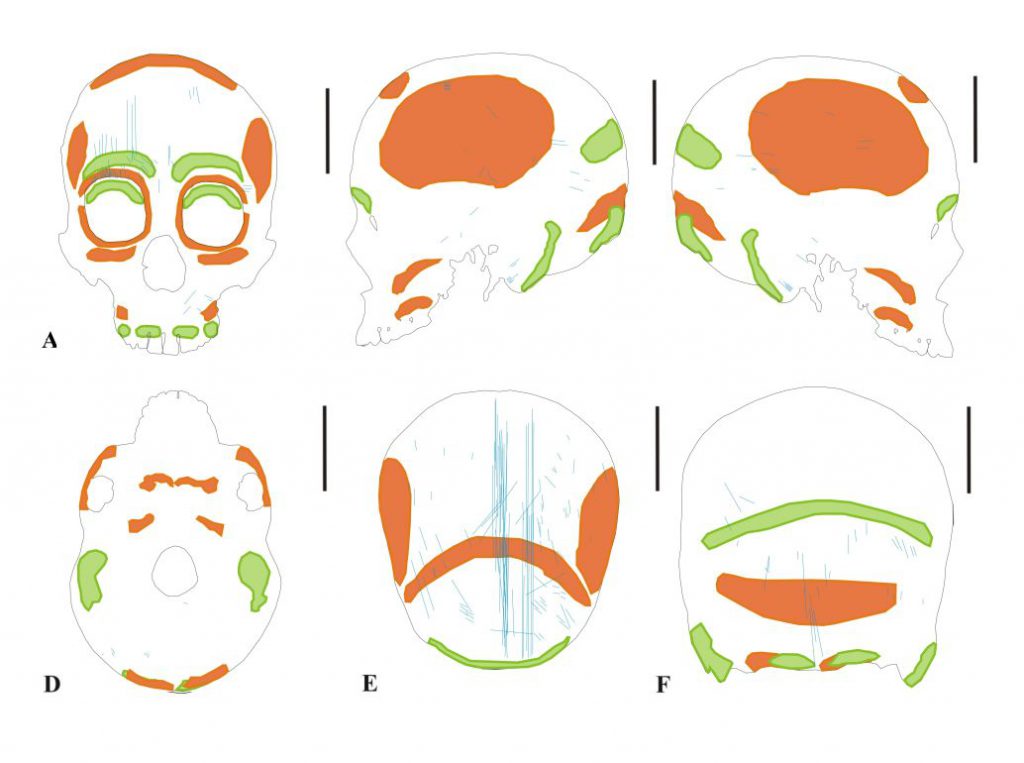

The study considered the bone as a map on which surface modifications are distributed and where it can be assessed whether if it is possible to identify specific patterns on the elaboration of cup skulls, by comparing evidences among the different sites mentioned above. Specific modifications related to this human behaviour have been identified and the relevance of the cut marks location in specific areas of the skulls has been statistically described. Signals made by using stone tools, when meticulously and repeatedly extracting the scalp and meat., Actions that indicate an intense cleaning of skulls in the specific cases of Gough’s Cave, Fontbrégoua, Herxheim and El Mirador. However, this model has not been observed on the remains of Homo antecessor from level TD6.2.

Systematic fabrication of the skulls began with the removal of the scalp and continued with the removal of muscle tissue. The elaboration of the skulls ended fracturing them to preserve the thickest part of the cranial vault. The use of these container-shaped bones is still unknown. The repetition of this observed pattern provides new evidences of skulls preparation for ritual practices, and are associated in most cases to human cannibalism during recent Prehistory.

Reference: Marginedas, F., Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A., Soto, M., Bello, S.M., Cáceres, I., Huguet, R., Saladié, P., (2020) Making skull cups: Butchering traces on cannibalized human skulls from five European archaeological sites. Journal of Archaeological Science. 114: 105076