12/03/2025

Atapuerca rewrites the history of Europe’s first inhabitants

A study led by the IPHES and involving the URV assigns the oldest human remains found at Atapuerca to the species Homo affinis erectus and confirms that Western Europe was populated by two species of hominin more than a million years ago

A study led by the IPHES and involving the URV assigns the oldest human remains found at Atapuerca to the species Homo affinis erectus and confirms that Western Europe was populated by two species of hominin more than a million years ago

A human skull fragment discovered at the Sima del Elefante site at Atapuerca has become the oldest face in Western Europe. The remains have been dated to between 1.1 and 1.4 million years ago and provide crucial insights into the early migrations and evolution of hominins in Europe during the Early Pleistocene, hominins being a subfamily of hominids to which the genus Homo (i.e. humans) belongs.

More erectus than antecessor

During the 2022 excavation campaign, the Atapuerca Research Team recovered several fragments from the left side of an adult individual’s face from level TE7 at Sima del Elefante. Reconstructing these fragments required meticulous work, combining traditional conservation and restoration techniques with advanced imaging and 3D analysis tools.

After two years of research, a detailed analysis of the individual —catalogued as ATE7-1 and named Pink by the researchers, has revealed that the face does not belong to Homo antecessor, the species identified in other areas of the archaeological site of Atapuerca, but rather to a more primitive hominin. However, the available evidence is insufficient for a definitive taxonomic classification. As a result, the individual has been provisionally assigned the name Homo affinis erectus, meaning similar to or related to Homo erectus.

“Homo antecessor shares with Homo sapiens a more modern-looking face and a prominent nasal bone structure, whereas Pink’s facial features are more primitive, resembling Homo erectus, particularly in its flat and underdeveloped nasal structure”, explains María Martinón, director of the National Centre for Research on Human Evolution (CENIEH) and one of the principal investigators of the Atapuerca Research Project. The researcher emphasizes that “the evidence is still insufficient for a definitive classification, which is why we adopted the name Homo affinis erectus”, in order to “acknowledge Pink’s affinities with Homo erectus while leaving open the possibility that the remains may belong to another species“.

Dated between 1.1 and 1.4 million years old, the ATE7-1 fossil is significantly older than the remains of Homo antecessor located so far at the site, estimated to be around 860,000 years old. This chronology suggests that Pink belonged to a population that arrived in Europe during a migration wave predating that of Homo antecessor.

This discovery not only enhances our knowledge of Europe’s earliest inhabitants but also raises new questions about the origin and diversity of the hominins who lived there. Dr Eudald Carbonell, co-director of the Atapuerca Project and professor emeritus at the URV, considers that “evidence for different hominin populations in Western Europe during the Early Pleistocene suggests that this region was a key point in the evolutionary history of the genus Homo”.

Environment and Lifestyle

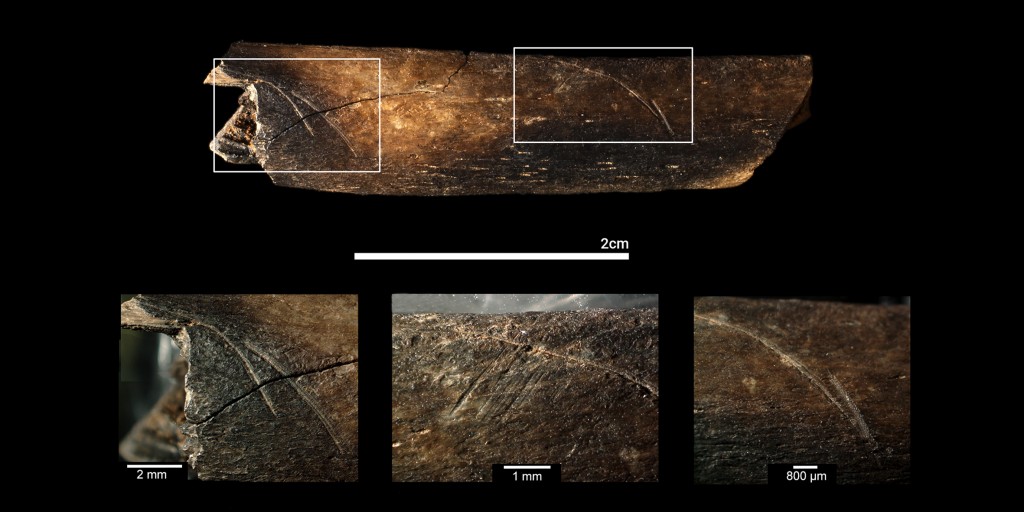

Level TE7 of Sima del Elefante where ATE7-1 was discovered, contains abundant evidence of the presence and activity of hominins during the Early Pleistocene. Among these findings, researchers have recovered stone tools and animal remains with cut marks, pointing to the use of lithic technology for processing animals.

For Xosé Pedro Rodríguez, URV researcher and a specialist in lithic industries, although the quartz and flint tools found are simple, “they suggest an effective subsistence strategy and highlight the hominins’ ability to exploit the resources available in their environment”. Cut marks identified on animal remains provide clear evidence that these tools were used to butcher carcasses. Rosa Huguet, an IPHES researcher specialising in taphonomy (the study of fossilization processes) and who led the research, considers this as proof that “the first Europeans had an intimate understanding of the animal resources available and knew how to systematically exploit them”.

By studying the organisms and environments present in the fossil and stratigraphic record at TE7, the researchers were able to extract paleoecological data which suggests that the Early Pleistocene landscape of the Sierra de Atapuerca was a dynamic environment, featuring a mix of wooded areas, wet grasslands, and seasonal water sources, thus creating a resource-rich habitat for these early human populations.

A key milestone for the Atapuerca project

The discovery of ATE7-1 represents a major milestone for the Atapuerca Project and for our understanding of the human settlement of Europe. “It is crucial for understanding our origins, and this new discovery further solidifies Atapuerca’s position as a global leader in the study of human evolution”, noted Marina Mosquera, director of the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA). Jose María Bemúdez, co-director of the Atapuerca Project, celebrated the discovery and predicted the start of “another prodigious era for the project”.

The research team expects that future discoveries and analyses will help refine our understanding of the origin and dynamics of early human settlement in Europe. Excavations at the Atapuerca sites, funded by the Department for Culture, Tourism and Sport of the Castilla y León region and supported by the Atapuerca Foundation and its patrons, and research into these findings, backed by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, could provide further data on the migratory waves that shaped human history.

The analysis of the findings has been published in Nature and was led by Rosa Huguet, researcher at the IPHES-CERCA, associate professor at the URV and co-coordinator, alongside URV researcher Xosé Pedro Rodríguez-Álvarez, of the excavation and research efforts at Sima del Elefante. The study is the result of a collaborative effort involving a diverse team of researchers and technical staff from the IPHES-CERCA and the URV, along with national and international institutions, most notably the National Research Centre on Human Evolution.

Reference: Huguet, R. et al. The earliest human face of Western Europe. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08681-0